The Geology Department successfully completed its Fall 2016 Departmental Trip to Virginia’s Eastern Shore last weekend, but the difference between Friday and Saturday were striking.

On Friday afternoon we rolled off campus amidst bright sunshine, warm temperatures, and a gentle wind from the East. We were bound for Virginia’s Eastern Shore — the southern end of the Delmarva Peninsula. Our group included a large cohort of young students, and an intriguing mix of veteran Geology majors.

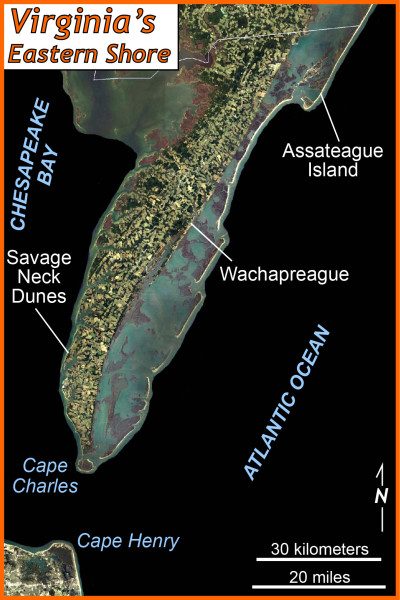

Our first stop brought us to Savage Neck Dunes at the Chesapeake Bay’s eastern shore. Here 15 to 20 meter tall sand dunes form a distinct landscape at the edge of the Bay; these dunes cover older strata and buried an ancient forest. Erosion along the modern coastline neatly exposes these geological relations. The waters of the Bay were calm, and a number of us took a mid-October swim.

Yet, off to the west a high wall of gray cloud was sliding eastward. A big, bad cold front was en route.

We spent the evening safely ensconced at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science’s Eastern Shore Laboratory in Wachapreague. Dinner was a multi-course affair, and quite a production with nearly 40 of us in house.

On Saturday morning we awoke to gloomy rain and wind. The cold front had passed, but its trailing edge was a menace.

Our original plan had been to take boats from the field station to the marshes and barrier islands facing the Atlantic, but the wind was blowing with vigor (>25 knots) from the north-northwest. Time to go with plan B.

Plan B involved an extended stay in the field station’s seawater lab, where we discussed the geologic history of the Delmarva Peninsula with its ancient scarps and mysterious Carolina bays. We also reveled in a wealth of live critters from the marshes and waterways (including urchins, oysters, corals, and snails – oh my!).

We then bundled up and headed to Assateague Island to witness modern processes at work on barrier islands. And on this windy Saturday those processes were working! The stiff north-northwest breeze blew sand along the beach and took the foamy tops off the waves.

Based on historic imagery we calculated that the beach at Assateague has eroded westward some 150 meters in the past 20 years, and in the process is rolling over the back-barrier marsh. Our beach trench revealed the layered three-dimensional structure of the shoreface sediments and we discussed the origin of the heavy mineral layers. We chucked grapefruits into the Atlantic Ocean- watching and measuring their progress as they moved parallel to the coast. Sediment is also transported parallel to the shore and at Assateague Island it generally moves to the southwest forming the exquisite spit at the island’s southwest end.

Our last stop was an old beach ridge complex that underlies the Assateague lighthouse. In 1833, when the original lighthouse was constructed at this site, this beach ridge was along the coast. In the intervening 180 years longshore processes, moving sediment to the southwest, have created the modern spit and moved the beach ~2 km from the lighthouse. Barrier islands are landscapes in which dramatic change can happen at the timescale of a day (the arrival of a hurricane) to a few decades, and as such are best left undeveloped.

Unfortunately, large swathes of barriers islands on both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts are developed and in grave danger.

As we traveled back to Williamsburg, the last of the clouds eased off and blue sky reigned. The cold front had changed our trip, but helped make the dynamic connections between the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and solid earth more evident.

This is my 20th year at William & Mary, and I remember my first department field trip on the faculty back in 1996: a trip that was also interrupted by a merciless cold front. Curiously, in talking with our Geology alums who weathered that 1996 trip, they seem to have only fond memories. I’m confident that our 2016 trip will be fondly recollected in future years.

Leave a Reply