The past month has been a blur as I’ve been away from campus most weekends doing geology with William & Mary students. I’m way behind getting these adventures posted, and this is the first in a series of posts intended to help me climb out of this virtual hole in the blogosphere. It’s been nearly two weeks since I returned from the Geological Society of America’s Southeastern section meeting. The meeting was held in Richmond, Virginia, which was effectively a home game for the Tribe — I’d never attended a proper scientific meeting so close to home.

The Society just published a guidebook with seven contributions that highlight Virginia’s geology From the Blue Ridge to the Beach. If you are interested in learning more, or better yet seeing Virginia’s exceptional geology, check this volume out.

My meeting started early, as my former research student Anna Spears and I led a field trip which took 21 participants from the ancient continent of Laurentia to the Iapetus Ocean — well, sort of! Laurentia was an ancient continent — and its 1 billion-year old granitic rocks crop out in the Blue Ridge. The Iapetus Ocean formed some 550 million years ago and then disappeared during tectonic collision later in the Paleozoic, however its story is preserved in the rock record. The trip’s high point (literally) was at Rockfish Gap along the crest of the Blue Ridge. Just below the Gap we also visited the Blue Ridge Tunnel, a 19th century engineering marvel that punched through the rocky interior of the Blue Ridge and exposed much of the wonderful geology (more on that in a near-future post).

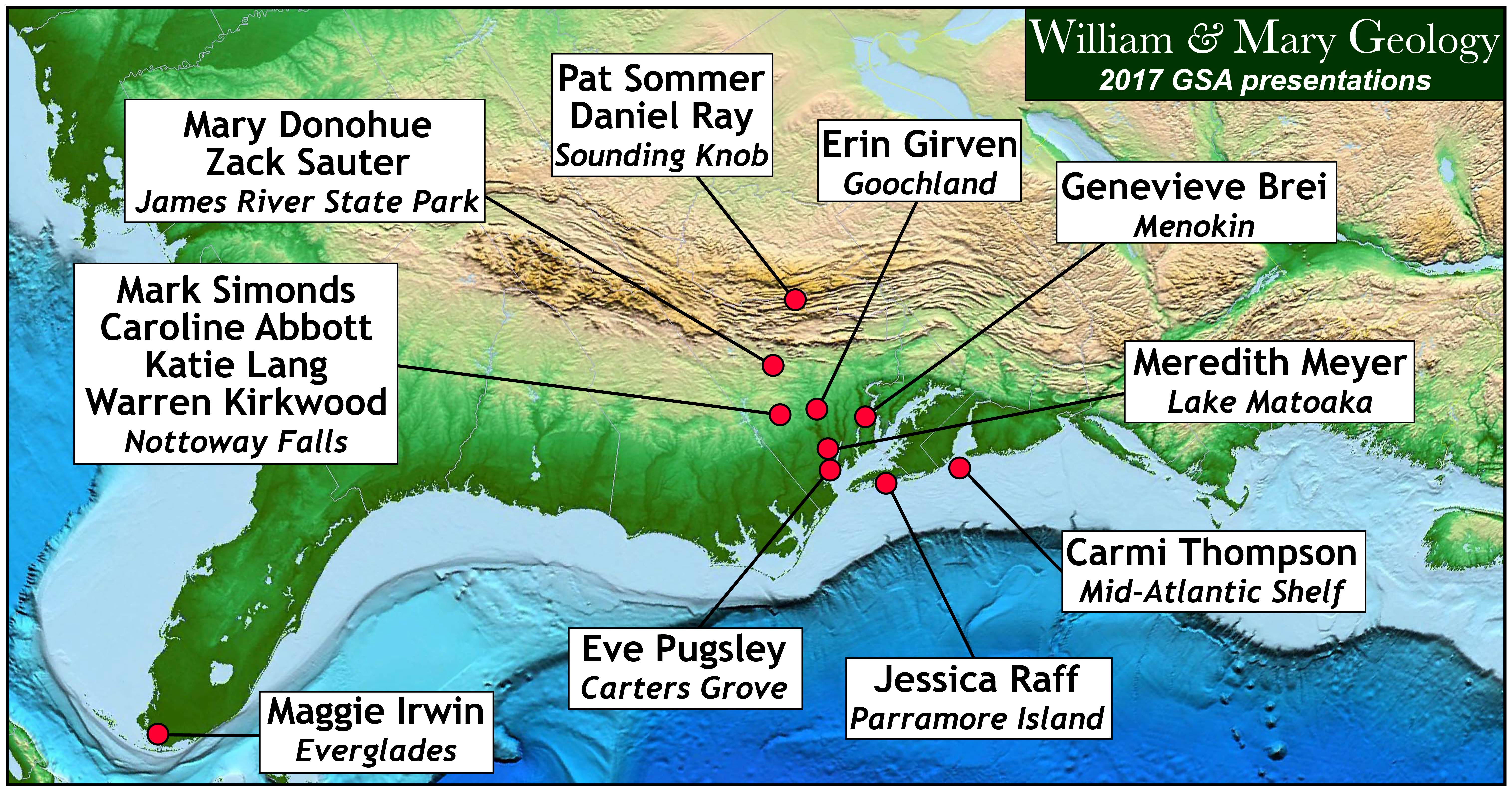

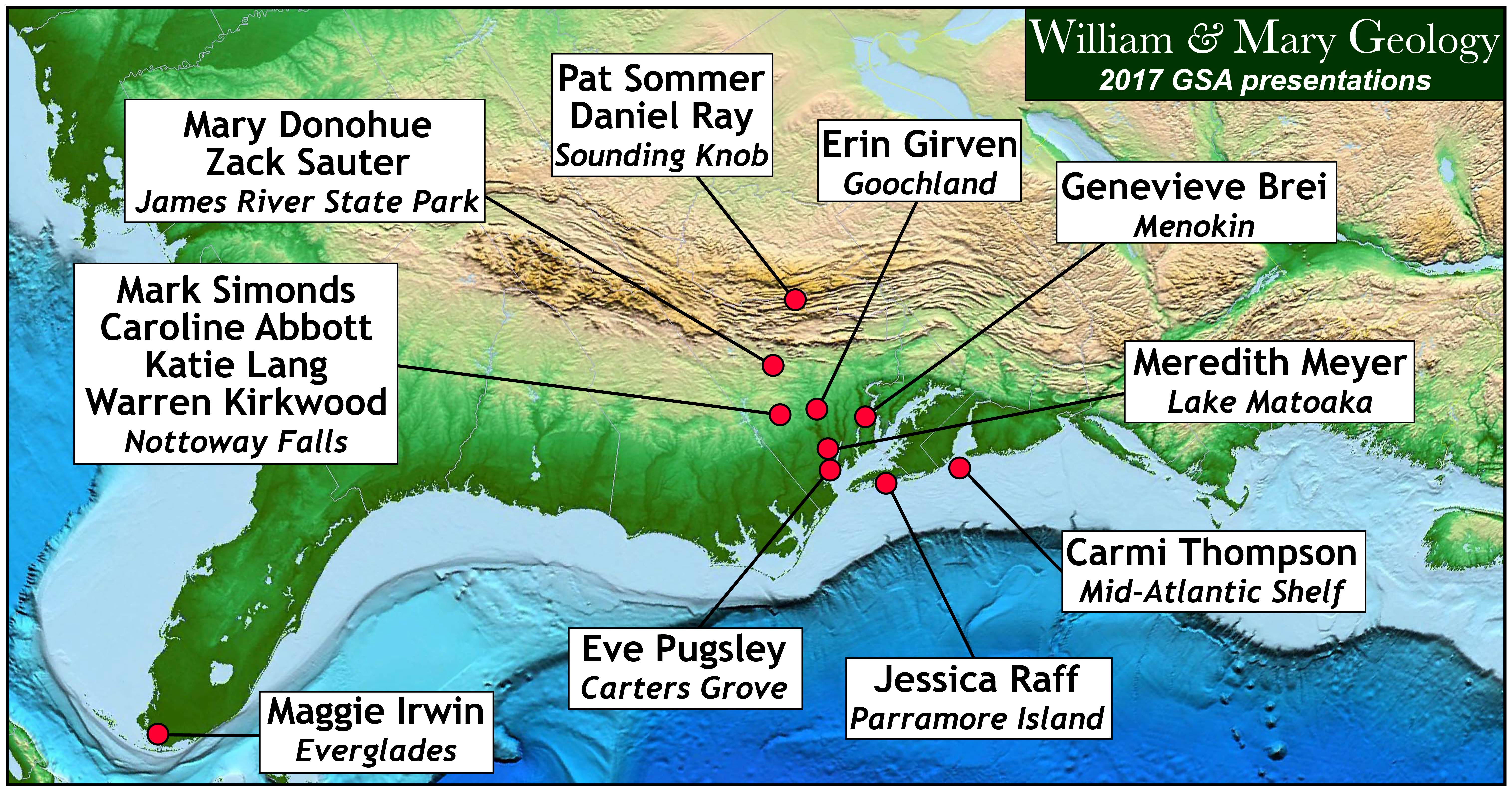

The meeting itself was a rush, and the William & Mary Geology department was well represented. Fifteen W&M undergraduates presented the results of their research at this conference. Their research focused on study areas in the eastern United States, but their work cuts a broad disciplinary swath from petrology to barrier island dynamics to archaeological geology.

I chaired a session and gave two talks — one focused on geological terranes in the central Appalachians, and the other on the Battle of Green Spring that occurred on the outskirts of Williamsburg during the American Revolution. The takeaway message from my second talk was: be wary of British redcoats hiding behind Pleistocene scarps. It was a rewarding and hectic meeting. I’m proud of how the William & Mary students accorded themselves, and truth-be-told the high point of the conference was seeing our students present their science.

After the meeting I co-led another field trip with my colleague Brent Owens and Mark Carter from the U.S. Geological Survey. This trip examined the Petersburg batholith, a massive complex of granitic rocks that oozed into what would become east-central Virginia some 298 to 300 million years ago.

The first stop was the low point (literally) of the whole experience. The Luck Stone corporation facilitated our Saturday morning visit to their quarry on the south side of Richmond. This quarry, by any standard, is an impressive hole in the ground, and it is situated just 200 meters (660’) from the James River. Here the James River is at sea level and forms a tidal estuary. The Luck Stone quarry is the easternmost rock quarry in Virginia, and it’s exceptionally well situated to ship huge blocks of granite on barges eastward to Tidewater Virginia. Virginia’s Tidewater region is on the Atlantic Coastal Plain, and is a sediment rich, but rock poor region. Many of the enormous stone blocks quarried here are used to armor shorelines and fend off coastal erosion.

The bottom of the Luck Stone quarry is 100 m (330’) below sea level — making it the lowest point on the earth’s surface in Virginia. Check any encyclopedia (or better yet, Wikipedia) and you’ll learn that the lowest spot in the United States is Badwater Basin in Death Valley, California at 85 m (-279’) below sea level. Luck Stone’s Richmond quarry is lower than the the lowest natural point in the United States — that’s both cool and a testament to the power humans have to modify the Earth’s surface.

It’s also impressive that at the bottom of the quarry it is dry, because the James River, chugging along with its 50,000+ gallons of water per second, is right next door and 100 m above the quarry floor. In essence the rocks of the Petersburg batholith are impermeable, and the fracture network is not connected to the surface waters. The Earth’s geological structure is important.

Here are the titles and links to the William & Mary students’ abstracts:

Mark Simonds, Caroline Abbot, Katie Lang, Warren Kirkwood, and Christopher Bailey

PROVENANCE OF FERRUGINOUS SANDSTONE AT MENOKIN ON THE NORTHERN NECK PENINSULA, VIRGINIA

Genevieve Brei and Christopher Bailey

INVESTIGATING EVIDENCE FOR STORM-INDUCED OVERWASH DEPOSITS IN A POND ALONG THE JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA

Eve Pugsley, Nicholas Balascio, James Kaste, and Linda Morse

EVALUATING POSSIBLE HIGH-P AND T AMPHIBOLITES IN THE GOOCHLAND TERRANE, PIEDMONT PROVINCE, VIRGINIA

Erin Girven and Brent Owens

Patrick Sommer, Daniel Ray, and Christopher Bailey

THE GEOLOGY OF THE JAMES RIVER STATE PARK, EASTERN BLUE RIDGE/WESTERN PIEDMONT, CENTRAL VIRGINIA

Mary Donohue, Zachary Sauter, and Christopher Bailey

A SEDIMENTARY RECORD OF ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE SINCE 1720 FROM LAKE MATOAKA, WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Meredith Meyer, Kassie Smith, Nicholas Balascio, and James Kaste

SURVEY OF MOLLUSCAN FAUNA FROM THE OFFSHORE MID-ATLANTIC UNITED STATES

Carmi Thompson, Kelvin Ramsey, and Rowan Lockwood

Margaret Irwin, Lynn Wingard, Rowan Lockwood, and Bryan Landacre

Jessica Raff, Justin Shawler, Daniel Ciarletta, Christopher Hein, and Emily Hein

Leave a Reply